Setting the scene

Before we dig deeper in the topic of an architectural tenet, it’s important for me to set the right scene for this topic. For some of you this whole topic may sound ridiculous and very obvious. Some others may be aware of everything that will be covered by this article, but know that in real life - because of several reasons - things went into other directions. Let’s try to find strategies to overcome such misleading impulses and try to be within the spectrum of technical debts that won’t kill you in the future.

I am confident that everyone of you is aware of what technical debts are. In general I would state that outside the perfect world, where there is no timeline, commitment, budget, … there are always technical debts - and this is ok. The more important question in this context is how fundamental such debts are. Does it limit the non functional requirements, does it minimize the maintainability or robustness, …? And exactly this is the real reason behind this article.

The difference within the concept of an Analytics Warehouse in comparison to a traditional app you build is that you combine things together (well known patterns, futuristic concepts and leading edge technology) that offer plenty of possibilities to go off the track. Now, the tricky question for you is to find tracks that are off the main road but aren’t blind lanes and follow only them - if it is necessary.

To be honest - while we were building our Analytics Warehouse, we went through a lot of off-track roads - sometimes also blind lanes. And we will in the future - I am very confident. But while doing so, we learned strategies to be better in the future - and such strategies we want to share with you.

Difference between a tenet and software requirements

TODO

Why do we need a tenet?

If the team that you are part of delivers something that needs to match into a bigger picture, then it is crucial that not only functional but also technical borders are being clearly defined. Such architectural borders don’t need to be insane specific, but need to build the umbrella to prevent unwanted side effects in the future, e.g. high costs to run the app, complex to add features, lack of skills on the engineering side, … . – transition isn’t smooth In the end we want to build something that fits the requirements, is easily integrable, is low in costs and meets the timeline.

Let’s take an example: The requirement for 3 components (A, B, C) is to process and visualise a huge amount of data (max. 10 GiB / sec, avg. 5 GiB / sec). If the components are isolated, A and C are able to process up to 10 GiB / sec. Component B is only able to process 5 GiB / sec.

At a first glance, we could say that component B may be a potential bottleneck because it is only possible to process the average amount of data that is determined. Now consider the architectural tenet into the game: Component A and B are within the tenet, C isn’t. To be more precise let’s assume we have a quite broad tenet that is like ‘everything needs to be built within ONE cloud’. Therefore component A and B is cloud based, C is built on some on-prem system. Someone that determined the architectural tenet knows that the connection from on-prem to the cloud is only 3 GiB / sec.

Now we have a deadlock. The team that built component C fulfilled the requirements except the tenet. The team that delivered component B had probably some challenges to deliver the 10 GiB to the specific end date, but fulfilled the architectural tenet.

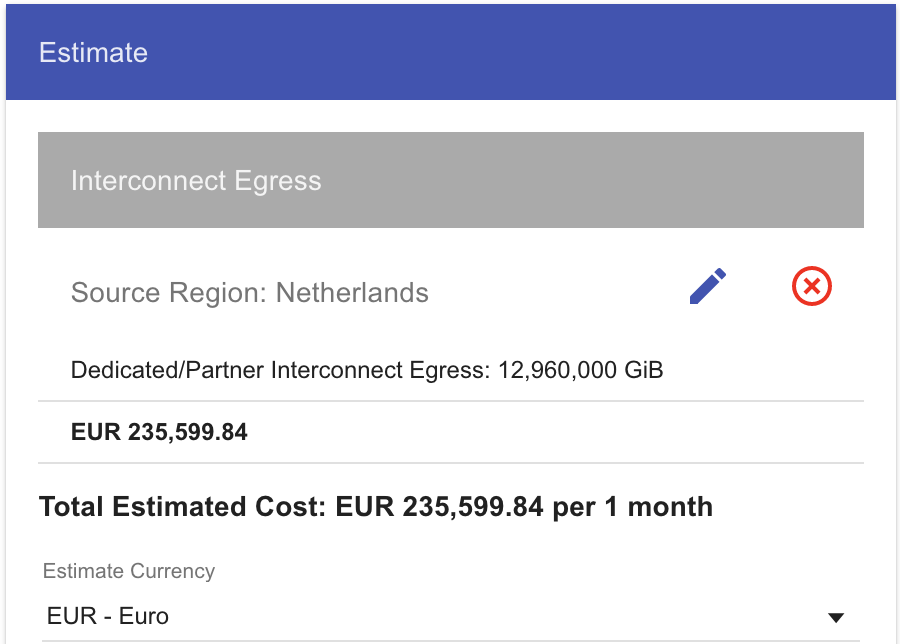

Let’s go back to the metaphor of the first section - the way off-road and the blind lines. Team B may have had such technical requirements for the first time and invested time in finding the right tools to go. Tradeoff is that the requested bandwidth couldn’t be delivered 100% to the end-date. Team C didn’t have a look at the cloud at all because they know how to implement such requirements in the on-prem environment. Team B chose the way off-road, Team C the blind line. Why? Because although the isolated component could process the amount of data that is requested, the amount of data couldn’t be sent to the destination in such volume. Therefore Team C delivered not 10 GiB / sec, but only 3 GiB / sec. One could argue that we could easily increase the bandwidth from the cloud to on prem (from 3 to 10 GiB / sec). Of course, this could be a possibility to bring component C back into the game. An fundamental argument against this are costs. Egress is something cloud providers charge you - especially if it is a high volume of data, costs can be enormous. To give you a sense of how much this could be, let’s assume we have an average egress of 5 GiB / sec for 30 days 24 / 7. This would be a massive number of 12656 TiB per month. (5 (GiB) * 60 (sec) * 60 (min) * 24 (h) * 30 (d)). While choosing a partner interconnect in the europe-west4 (Netherlands) region, this would cost us around 250k €.

I think, at the latest, this huge number convinced you that Team C’s way was a blind lane. Overall, I hope that the example could emphasize how important an architectural tenet is. The reason why I choose this very easy situation is to showcase the core message. In the next section we will go into more details with a real life example of an off-road and a blind lane situation.